Joachim Aviron: a Forgotten Modernist

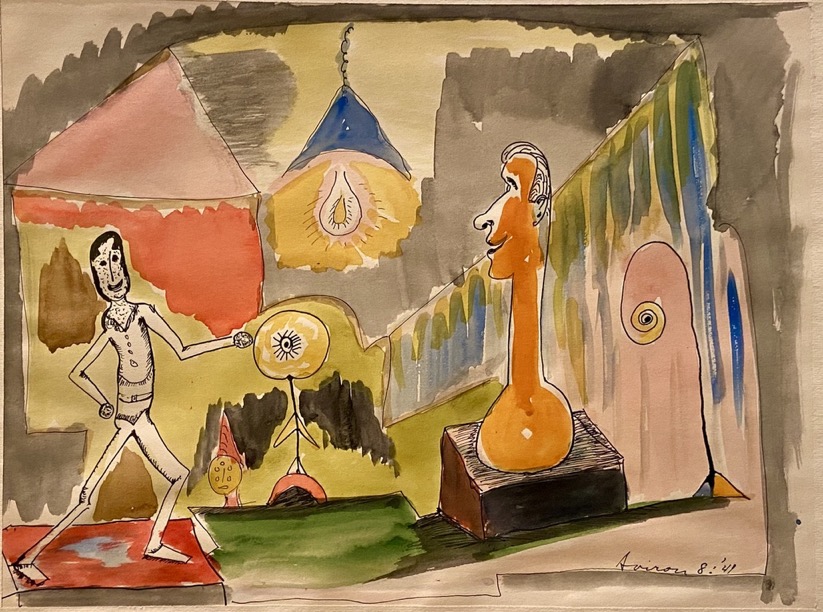

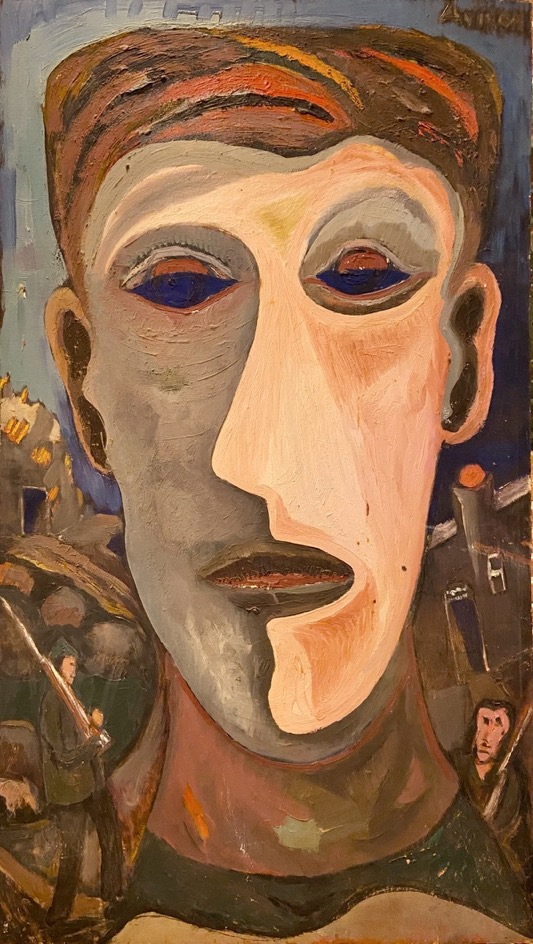

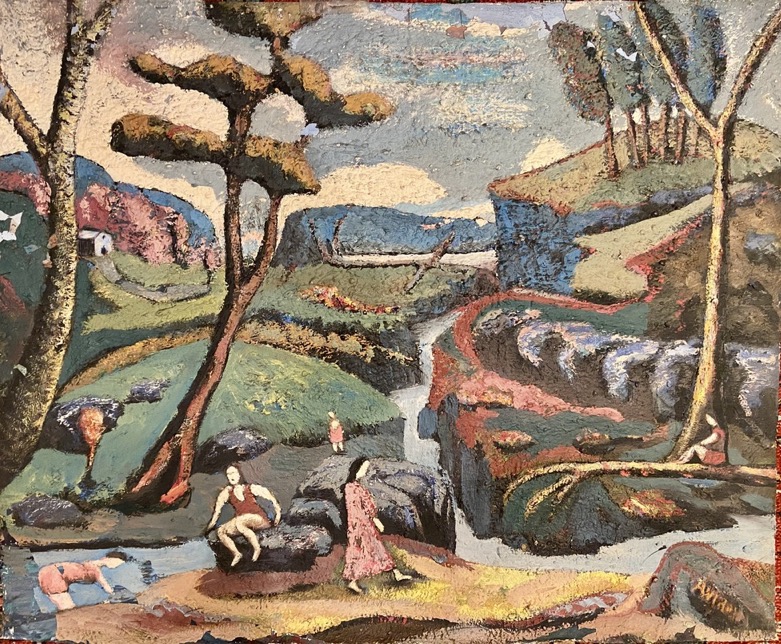

Mr. Aviron did not paint for an audience. Instead, Aviron painted for himself. Perhaps the truest form of expression. He painted because the desire to express himself as an artist overtook the need to present a work that would be what was expected of him. Mr. Aviron painted the unexpectedness of his reality. A reality that formed around him. One in which every detail was present, accounted for and celebrated. Mr. Aviron continued to paint, to write, to teach. With his wife by his side, the Aviron's continued together along Joachim's path of creativity. He continued to paint his reality, But by 1944, Mrs. Aviron reached out for help. Bertha began to notice changes in her husband. And so she acted in the best interests of Joachim. Bertha contacted the Curator of the Brooklyn Museum, Mr. John L. Barr. Bertha asked Curator Barr for suggestions on where to present the works of her husband. Mr. Barr directed her to contact Assistant Curator Dorothy Miller at the Museum of Modern Art. Upon receipt of her letter, Ms. Miller responded to Bertha's request for an audience for her husband.s paintings. Miller offered to view Joachim Aviron's work as soon as it was brought in to her office. This was Joachim's chance to place his work in front of an audience eager to see it. Ms. Miller had recently created her first of at least six curated art exhibits focusing on American artists. Joachim Aviron had become an American citizen years prior. He could technically be in the running for consideration of her next show. So why then did the Aviron's not take Miller up on her offer. I can't say. But Mrs. Aviron did not give up on her husband or on her connection at the MoMA. And that is why in 1945, Mrs. Aviron wrote a second letter to Ms. MIller. This letter lacked the matter-of-fact tone that the first letter had. This letter was desperate. This letter spoke of depression, loss of hope and a lack of desire to live. It was a truly moving cry for help in which Bertha painted a picture of being surrounded by paintings that were not being seen by an audience other than the artist and his wife. Imagine being surrounded by what you love, what you have created and feeling as though it is swallowing you up. Mocking you. Reminding you that no one has seen your work and still pushing you to create more.

Had Aviron lost his will? Or was it a response to the current situation of World War II. Abstract Expressionism grew out of the visceral response to the war by a school of New York artists in the downtown scene. Aviron was living far out in Brooklyn, on the edges, the fringe, if you will. He was in Seagate and Coney Island. Perhaps being far removed from the activity of Manhattan, Aviron had created his own reality that threatened to consume him. Add on to that the response to a global war. A war that caused death and destruction. A war that had its own reality. Surely, an artist like Aviron would've had moments of despair. And perhaps his wife, while meaning well, could not understand this full body response. And I think that Curator Miller from the MoMA knew this. She resounded to Bertha's letter within a day. Miller did not focus on the hardships that Bertha perceived, but rather on what could be done. On galleries that should be contacted. On plans to make. On the hope to have in the reality that Aviron had created.

And so what had happened between 1945 and 1963? Did Joachim Aviron take Dorothy C. Miller's advice on what galleries to contact? According to a newspaper article from a local Brooklyn newspaper in 1963, the Aviron's had moved to Brighton Beach around 1956. Joachim's work had been exhibited in both the boroughs of Brooklyn and Manhattan, but records of those exhibitions are lost. He obviously continued to paint, to create and to live. He had not lost hope. He had not lost his will. He had not allowed his reality to consume. Rather, it appears that Joachim found a new desire to pursue his calling.