Hidden Messages

Why, you ask. Because I always bought something great from him and for my daughters it was because he always had Oreos. I call that a win-win. This painting was still unsold after the morning rush of dealers. You see at this time my family and I were living in Connecticut and I would often bring my girls with me to the market. Just not at 3am. More like 9am. Each snug in their half of the double stroller, we wound our way through the Garage looking for treasure. And Oreos. As soon as I saw this painting I knew I needed it. By now you know I love a mystery and this one posed a great sleuthing opportunity. Getting home I quickly went to my computer to begin the task of translating the work. It referred to a famous Russian Soviet poet, Vladimir Mayakovsky. Mr. Mayakovsky was a stand out figure in the Russian Futurist movement as well as supporter and critic of the Soviet State in the early 20th C. Quite a dangerous tightrope to walk if you ask me. The word on the top left is Chai followed by the word for This. Then at the top you’ll see Vladimir Mayakovsky and under it the word for All Right or Nice! Scrolling down you’ll see the word Pravda, which as you know is both the word for truth and the name of the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. What you may not know is that by adding those letters before and after, the artist changed the meaning of Pravda from truth to untruth. While Mayakovsky died by his own hand some 61 years before this painting was created, this artist aptly told his story through a painting of a deconstructed samovar. With each piece that I buy I am presented with an opportunity to learn, but sometimes it’s the memories of the experience that stay with me. Because every time I think of this painting, I think of my two little girls eating Oreos. ;-) hkv

Extra Information:

I always seem to be getting myself into situations that need an incredible amount of translation. Whether it's hopping on a plane to shop for antiques in Brazil (no, I didn't speak much Portuguese) or buying unsigned paintings (something I've gotten quite good at, if one can be 'good' at such things) or buying paintings from other parts of the world where English really isn't the norm. And that's where I was a few years ago. Translating a Russian painting. Wait a minute, did I say translating a painting? Yes. This particular work by contemporary Russian artist Anatoly Belkin is full of symbolism and words. In Cyrillic.

Looking at the painting one late morning at the New York City flea market (I couldn't go at my usual early hour), I knew that it was something special. I spoke with my friend about the painting and as antique dealers are apt to do, he tried to talk me out of buying it. "Heather, everyone has seen this already", he said. I bought it anyway. The business is a funny one and if a dealer thinks that all the 'right' people have already seen something and passed on it they sometimes lose a little faith in it. It only makes sense because we as dealers are buying on our own taste. If those choices are not validated by a sale, we begin to think that we made a mistake. It's just how the business works. But, back to the painting...

I asked my friend what it was all about and who the artist was. His only information was that it was a painting of a samovar and was full of Russian words. There are plenty of dealers at the flea market who speak Russian, but I chose to try my hand at translation. First though, I had to figure out who actually painted the painting. Signed with a monogram and dated 91, I couldn't wait to get home and begin my search. Trying a few different online sites, I finally found the one that gave me my answer (for just $25 per year). The monogram Ab is for Anatoly Belkin. Turns out he's alive and well and painting in Russia. He was born in 1953, went to art school in Russia and works in St. Petersburg. Great. Now, what does the painting say? Looks like another search is in order...

Found another great site, this one to translate the Cyrillic alphabet. Working the letters out and then searching again gave me my answers. Sort of. The painting says a lot about tea. And Soviet poets. And truth. Or actually un-truth. So, here goes. At the very top is the name of a famous Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. Mr. Mayakovsky was born in 1893 and lived a life that he cut short, committing suicide in 1930. Those years in between were filled with protests, jail terms, love affairs, poems, stage plays, friendships and so much more. He was close friends with David Burliuk and the two would explore Futurism in it's many veins. They were known to stand on street corners reciting poetry and throwing tea at their audiences. This was to annoy the bourgeois art establishment. From what I read, they were quite successful. In another refernce to tea, Mr. Mayakovsky is know to have said about Anton Chekhov, "Language is as precise as 'hello' and as simple as 'give me a glass of tea". There is also a famous poem by Mayakovsky where he commands the sun to stay with him and have a tea.

And what is all this talk about tea? Well, the samovar is the main focus of the painting. At the top left, there is the simple statement, "This is tea". And below that one reads the word for 'very good". It was all starting to come together. Sort of. And now for the truth, or rather un-truth. The newspaper Pravda features quite prominently along with the slogan, Workers of the World Unite! But what are the letters before and after Pravda? Well, the addition of those letters turn Pravda (truth) into un-truth or falsity.

So what does this all mean? Not sure yet. Literal translations of art are pretty superficial. The truer deeper meaning is in the understanding. And for that understanding, I spent some more time with the painting and my computer. Searching for the answers and the understanding.

An American Hero Comes Home

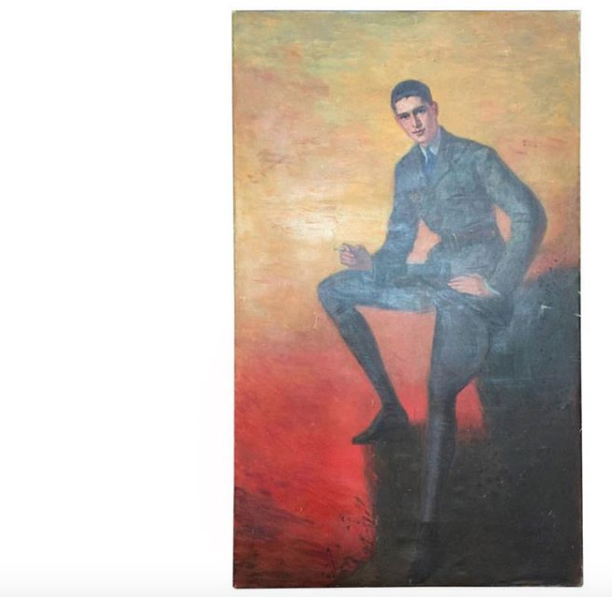

This painting tells the story of Henry Howard Houston Woodward. Born in Chestnut Hill in Philly and educated at Yale. Henry was a charismatic young man who gave his life so that others could be free. Serving first in the Ambulance Corps, Henry's superior officers saw his determination and grit. He was allowed to join the aviators and was soon flying missions. It was on one of those missions that Henry lost his life. His story will always be told though the power of art. I discovered Henry's identity through many late nights in front of my laptop. Even though the painting was signed by the artist Marie Eristoff Kazak, the sitter's identity was not mentioned. His World War I French aviators uniform was my first clue. This eventually led me to a book of his letters published by Yale University press called A Year for France. It was in this book that I found an image of the painting. Henry had written home to his parents and asked if they would wire him the money to have it painted - he wanted there to be a record of him should anything happen. His beautiful letters and this painting tell his remarkable story. This work is now in a Philadelphia area museum. ;-) hkv

Extra Information:

When it is a person. Wait. What? Okay, here’s what I mean. Back in the Summer of 2014 I attended an auction at the warehouse of a once prominent gallery. I was there for the picture frames and I bought about 250 of them. One of the last lots of the auction was a heavy cardboard tube that supposedly contained a rolled up painting. So, being the impulsive gambler and dreamer that I am, I simply kept my hand in the air till the lot was mine. Now I had to hope that there actually was a painting in it. I’ll skip over the excitement of loading a rental truck with 250 frames and then unloading all of them and get right to the good stuff... So, back at my showroom, I carefully removed the canvas from the tube and began to unroll it on my eight foot work table. And I unrolled it. And unrolled it. It was massive. A face was staring at me. A young man in uniform holding a cigarette in his hand staring right at me. Quickly I looked for a signature and found it only after the light caught it just the right way. I first saw a monogram of a crown and then the hyphenated last name Eristoff-Kazak. Fantastic. A signature often makes the research that much easier. Boy, was I in for a surprise. Turns out Eristoff-Kazak was actually Russian Princess Marie Eristoff-Kazak (born Etlinger Mariya Vasilevna later using the names Mary Kazak, Maria Eristova and Marie Eristoff Kazak) a painter of the Russian aristocracy. She was born in Saint Petersburg in 1857 and studied art with the Hungarian born court painter Mihaly Zichy. In 1887, Marie Etlinger married Georgian Prince Dmitry Eristavi. Mr. Zichy brought the Princess to Paris for the first time in 1890, she would later move there permanently in the early 1890’s and become a fixture on the Paris art scene. Her reputation grew and she became known for her portraiture of the Russian aristocracy visiting or living in Paris. The Princess had a long career in Paris, while also sending her work for exhibition to London and St. Petersburg. She died there in 1934. So, now that I’ve learned a bit about the artist I can begin the process of discovering the identity of the sitter. I’d like to digress for a moment and share a similar story about a portrait, a discovery and a story...

Earlier in the year, Colin Gleadell who is an art world reporter for the past 27 years and a regular contributor to many publications including writing a weekly column for The Daily Telegraph’s Art Sales page, reported on a portrait that sold at an auction in the countryside of London. While this would not normally merit inclusion into one of Mr. Gleadell’s columns, this was no ordinary portrait. The artist, Ambrose McEvoy - a London society painter who died in 1927, never really achieved high results in the auction world. Yet this portrait of an unknown woman (which carried a presale estimate of just $1067.) would bring $62,846. Whoa. They say, it just takes two to make a record. Boy were they right. But why all the interest you ask? And just who bought this work? I’ll tell you. Actually Mr. Gleadell coaxed the answers from the buyer, none other than Mr. Philip Mould a London gallery owner specializing in portraits. It seems that Mr. Mould has become quite well known for uncovering the identities of the sitters of the portraits he purchases. And this one was no different. The sitter was a Ms. Lois Sturt a British silent movie star who was born to a Baron in 1900 and died in 1937. Described by her biographer William Cross as a “wild child” and “the brightest of the bright young things”. There’s more to this story and if you want to read it, click here for the full article in The Telegraph. Just make sure to come back here and read why I thought it would be important to tell you about this story...

Now back to the painting in my inventory. Where were we? Oh, right. The Russian Princess artist. Seems she was quite the bohemian artist for being a Princess. Always giving of her work and her time. Living the life of an artist in Paris during the early 20th Century. But just how did she come to paint this portrait. And just who is he. I’ll tell you. Because Mr. Mould is not the only one who can uncover the identity of a sitter in a portrait. Turns out he is none other than Henry Howard Houston Woodward, part of the very prominent Houston Woodward family of Philadelphia (by way of Wilkes-Barre, originally from Connecticut). In 1917, Henry was enrolled at Yale University and set to graduate as part of the Class of 1919. It was during February of that year when Henry volunteered for World War I. He was shipped out to France just two months later. The ship carried him along with hundreds of other volunteers, cargo, trucks, supplies and more. The cross Atlantic journey was slow and Henry was chomping at the bit to arrive in France. Shortly after arrival, Henry’s section of drivers - the Ambulance 13 corps were placed on the front lines in some of WWI’s bloodiest battles. Henry’s bravery, intelligence and determination were quickly recognized and rewarded by his superiors. Henry wanted more responsibility and more action. He had begun training to become a pilot for the French and was quickly excelling in his classes. His hard work was rewarded with extra time off and he received additional days to spend in Paris. And this is where our story takes a turn.

It was in Paris where Russian Baron Eugene Fersen was escaping the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution serving as the head of a Russian Mission. The Baron, born in St. Petersburg in 1873, was the eldest son of a Grand Duchess who was a mistress to (it is reported) Czar Nicholas II (you know, the Bloody Czar...). He was quietly living in Paris and working on his manifesto which would later become the Light Bearers Society and the Science of Being (the Baron and his mother later moved to the United States, bought a gilded age mansion in Seattle owned by an imprisoned con man and used that as the headquarters for their society until his death in 1954). But, I’m getting ahead of myself. Back to Paris. The Baron was close friends with the Princess and offered a few rooms in his apartment for her to use as a painting studio. It was around this time that the Baron met Henry. The exact details of their first encounter are not known, but we do know that the two shared a very close and personal relationship. The Baron was quick to recognize Henry’s first rate character and Henry was enamored by the tales the Baron would tell of his family, his life in Russia and all that the Baron promised him after the war. The two spent as much time together as the war would allow. And it was on one of those weekends together when Henry met the Princess. She, too, recognized something special in Henry and asked if he’d like to have his portrait painted. She saw in him “an Egyptian face, ancient Egypt, that is, not modern”. The Princess painted Henry with “a classic mouth, long, straight nose, high cheek bones, and long sphinx eyes!”. And Henry knew that the Princess was “really a genius” and was “about the best portrait painter in Europe now, and in France for certain”. You could say that the two really hit it off. Henry had asked his family back home in Philadelphia for the 5000 Francs (about $1000 at the time) to pay for the portrait and said that “it would be a good souvenir in case anything did happen to me.”

Sadly Henry’s words would be prophetic. Just two weeks after having his portrait painted1918, Henry’s plane would be shot down over the small town of Montdidier, France. It was not until 1919 that the plane would be discovered. Henry’s family travelled to Montdidier sometime in 1920 to erect a monument to their son, help to rebuild a cathedral in the town that had been damaged in the war and to collect his personal belongings. This painting was among them. Once the belongings arrived back in the States, the painting was to remain rolled up. Forgotten. If not for that auction, Henry’s story would also have been forgotten. Now it will live on forever thanks to the Power of Art. Oh, and some detective work.